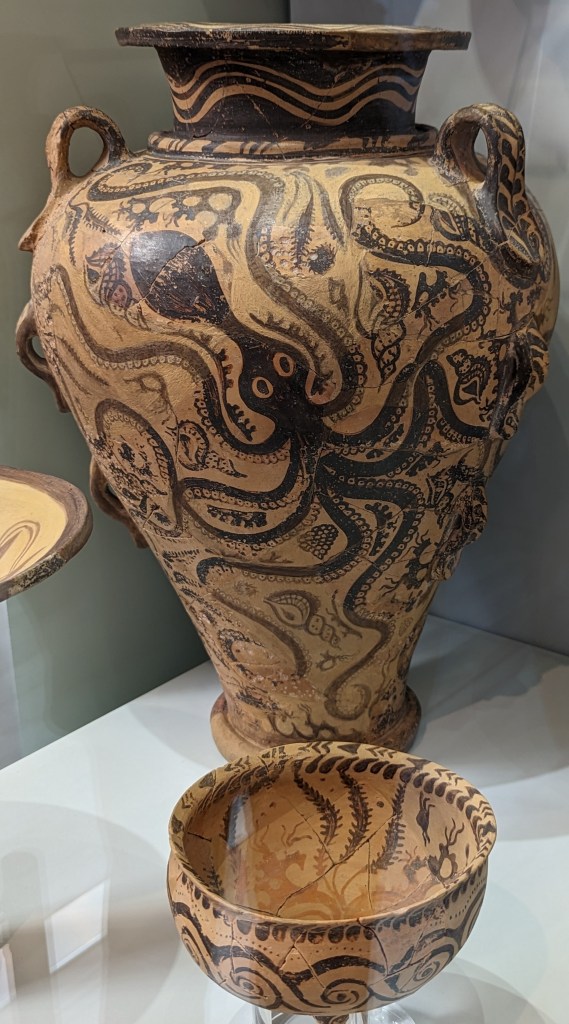

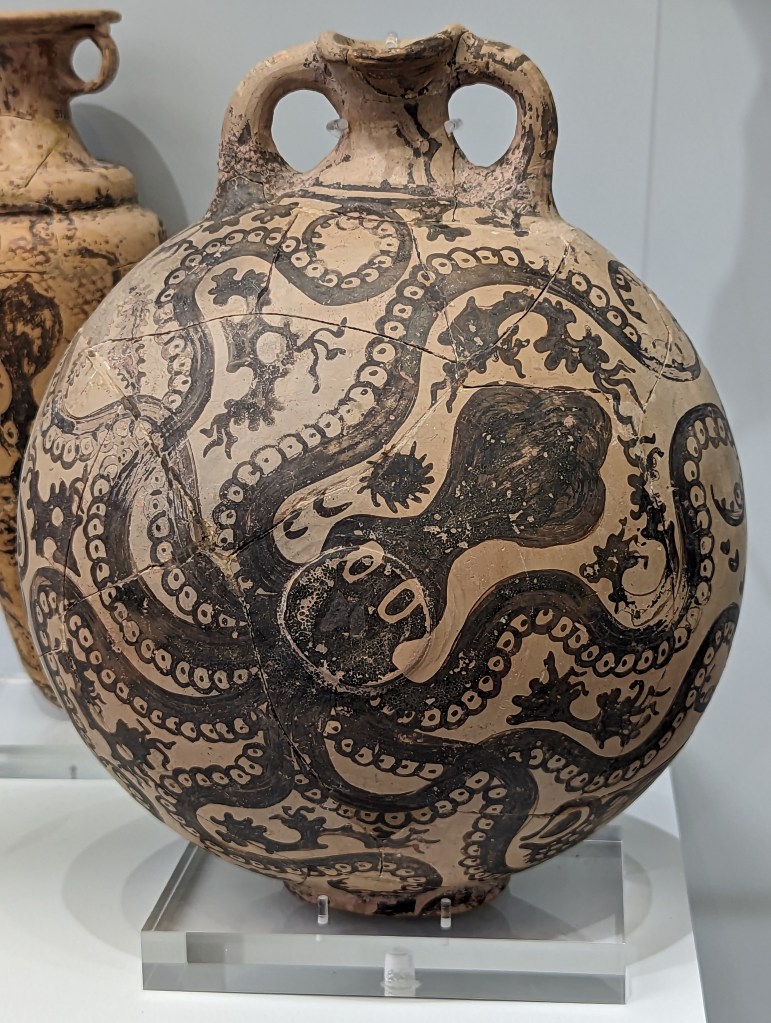

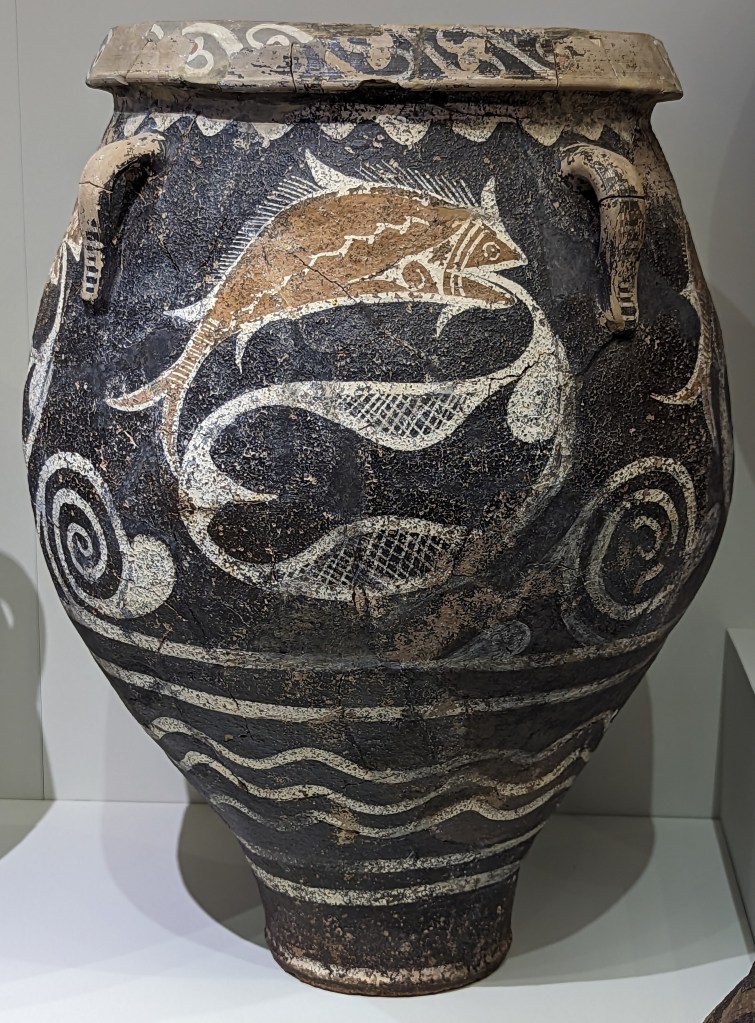

Crete is the largest island in Greece, home to Europe’s earliest recorded civilization, the Minoans (2700 to 1420 BC). As I’ve mentioned before, I love ancient Greek pottery, but I’m especially fond of Minoan pottery. Whereas Classical Greek pottery (480-323 BC) is quite formal and celebrates gods and heroes of war, Minoan pottery is playful and childlike and depicts plant life, animals and ocean creatures in naturalistic and abstract forms. The largest and best collection of Minoan art, including pottery, frescoes, jewelry, figurines, and sarcophagi, is in the Heraklion Archeological Museum on Crete, which was our first stop on our Viking Cruise excursion.

Minoan jewelry also represented nature and demonstrated the Minoans’ command of sophisticated technology influenced by Egypt and the East. They used an array of metals such as gold, silver, and bronze. Also semi-precious stones such as rock crystal, carnelian, garnet, lapis lazuli, obsidian and jasper.

One of the most famous exhibits in the museum is the gold Malia Bees pendant. It was found in a tomb in the Old Palace cemetery at Chrysolakkos, outside the Palace of Malia the third largest Minoan palace. The pendant dates back to the Bronze Age (1800-1700 BC) and depicts two bees carrying a drop of honey to their honeycomb grasped with their legs in the center. Bees were very important in the Minoan matriarchal civilization. They believed that the Great Mother Goddess was related to bees, representing mutual support and fertility. This pendant is evidence of the artist’s mastery of faience or granulation, the technique of soldering tiny pieces of metal on the surface of the cast jewel.

The image of the bull is found in many forms in Minoan art: jewelry, figurines, frescos, pottery, ritual pouring vessels and sarcophagi. In Greek mythology, King Minos, the ruler of Crete, dwelt in the palace at Knossos. He had his architect, Daedalus, construct a labyrinth, a very large maze to house his son, the Minotaur, a creature with the head and tail of a bull and the body of a man. The precise meaning of the bull image in the Minoan culture is speculative. But in other Mediterranean civilizations, the bull was the subject of veneration and worship, a symbol of power and fertility, and the life-giving power of the sun. So we can assume that Minoans also revered the bull in a similar way.

Minoan women appear often in Minoan art, showing their prominent role in Minoan society and religion. One example is the “Snake Goddess” excavated by the British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans from the Knossos Palace in 1903 in the form of three figurines. Evans called her the “Snake Goddess,” but her function remains unclear.

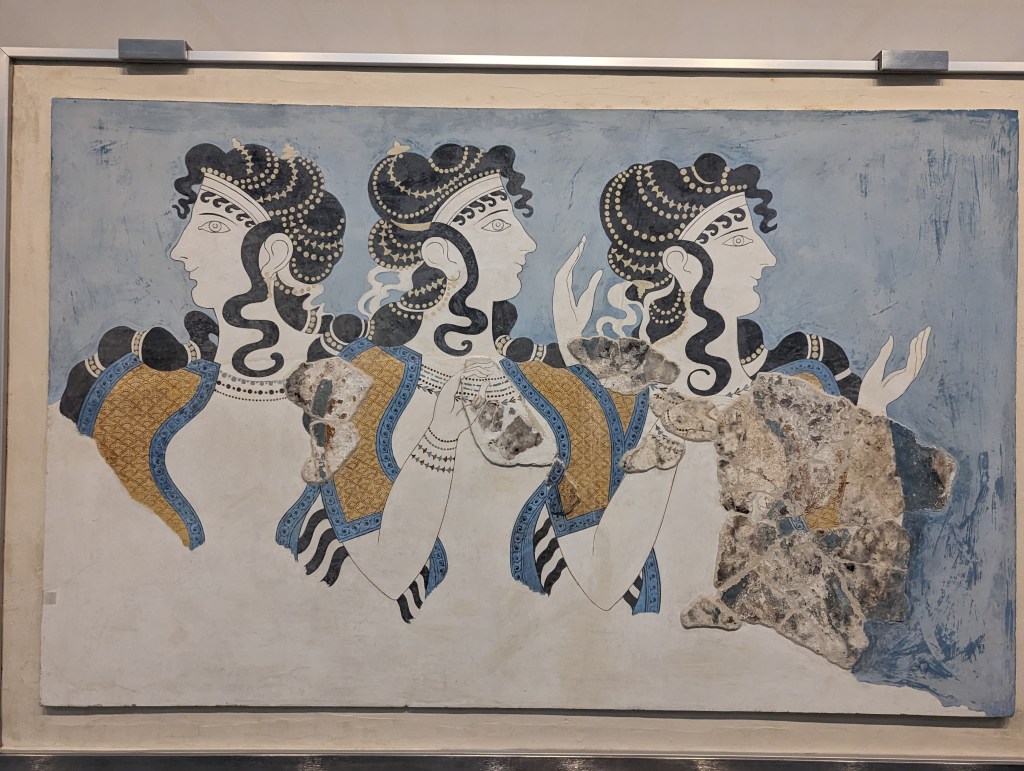

The “Ladies in Blue” fresco was also excavated by Evans from the Knossos Palace. The fragments were recreated by Emile Gillieron, a Swiss artist and archaelogist. These women might be goddesses as in the “Snake Goddess” or just noble ladies of the court. They are elaborately clothed and bejeweled. Their gowns expose their bare breasts which was typical of the Neopalatial period (1700 to 1450), a time of opulence and prosperity when the Minoans were at the height of their civilization.

“La Parisienne” fresco (1450-1300 BC), discovered by Evans at Knossos Palace, was so named by Evans because she reminded him of the contemporary women of Paris. The knot of cloth at the nape of her neck was, according to Evans, a sign that she was possibly a holy person, perhaps a priestess. This fresco is one of the few representations of Minoan people rendered in color and detail.

Perhaps the most famous of all the Minoan frescoes is the “Prince of the Lilies.” It was excavated by Evans in pieces from the Knossos Palace, and its reconstruction is in the museum. Much has been written about this fresco, debating his identity and function. Evans initially believed the figure was a boxer, but then changed his mind and called him a “Priest-King,” partly due to the plumed crown. The problem lies in the fact that very few fragments were found, so the reconstruction is controversial. For instance, the reconstruction shows the figure’s left hand is holding a rope which Evans thought might be leading a griffin or sphinx; others have suggested a bull. But the arm was never found, so there’s no evidence the hand was holding a rope at all.

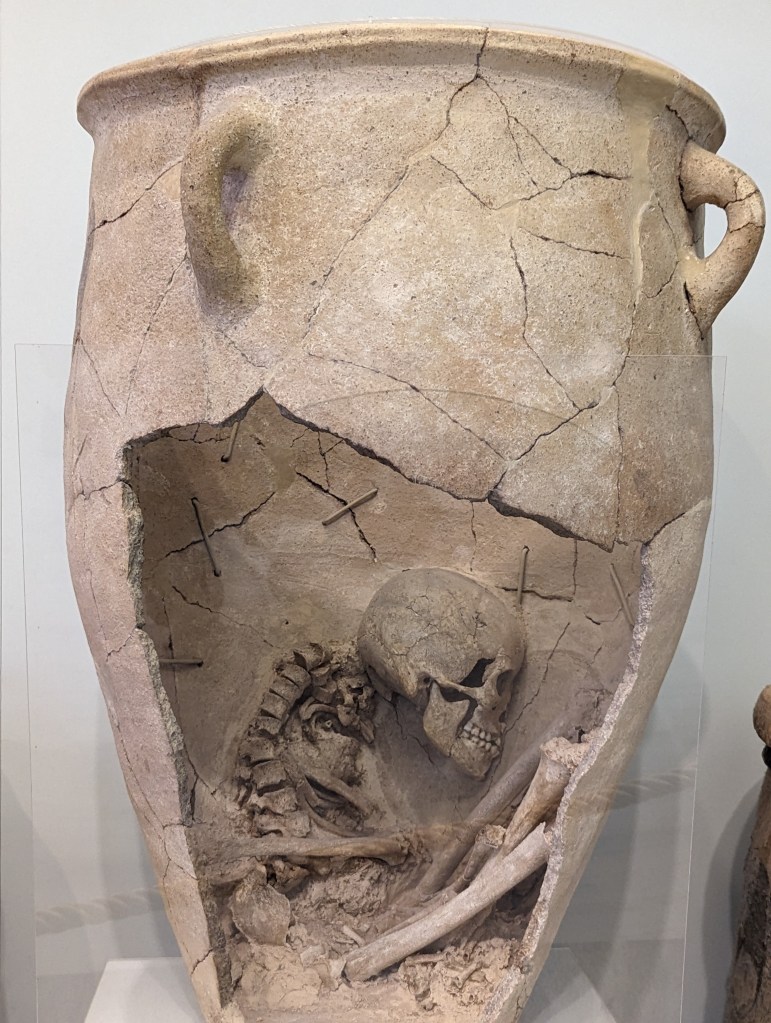

One of the most unusual objects at the museum was the burial pithos, a large jar containing a skeleton in a fetal position. Pithoi were mostly used for storing or shipping wine, olive oil, or grain. Burials in pithoi appear at the end of the Early Minoan period (2000 BC), almost at the same time as burials in a larnax (small closed coffin chest usually of terra cotta). Pithos burials were mostly used for children and infants.

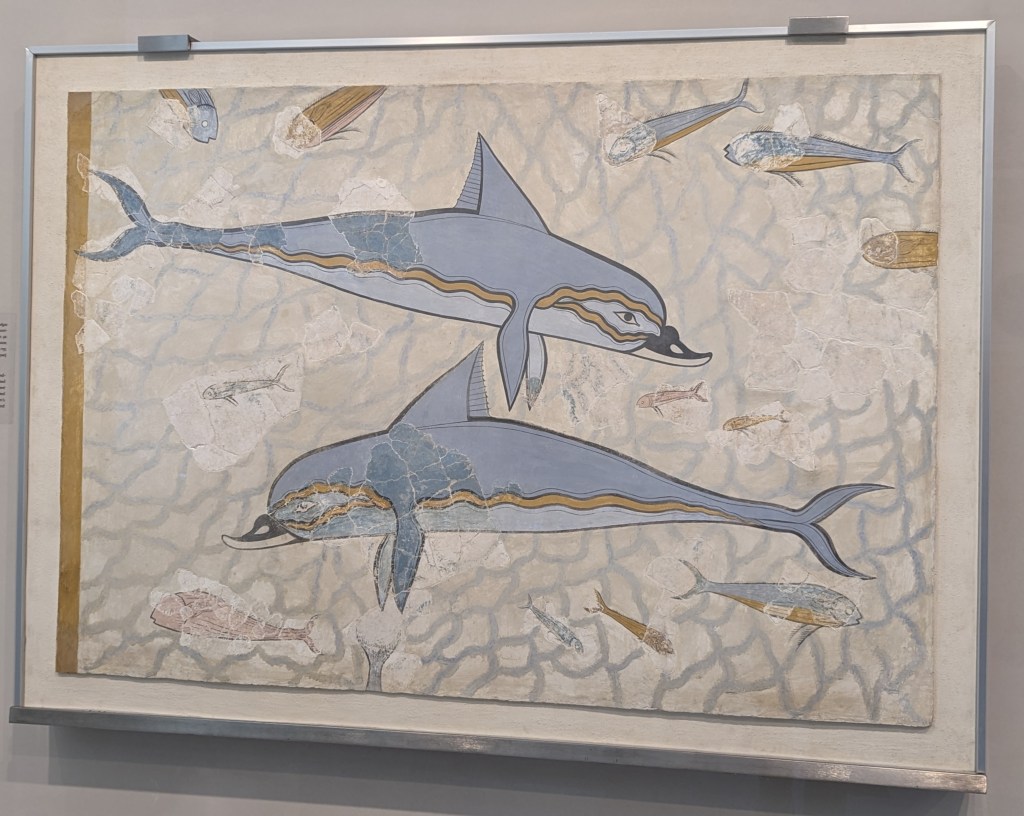

Minoan frescoes depicted a wide range of subjects of the natural world.

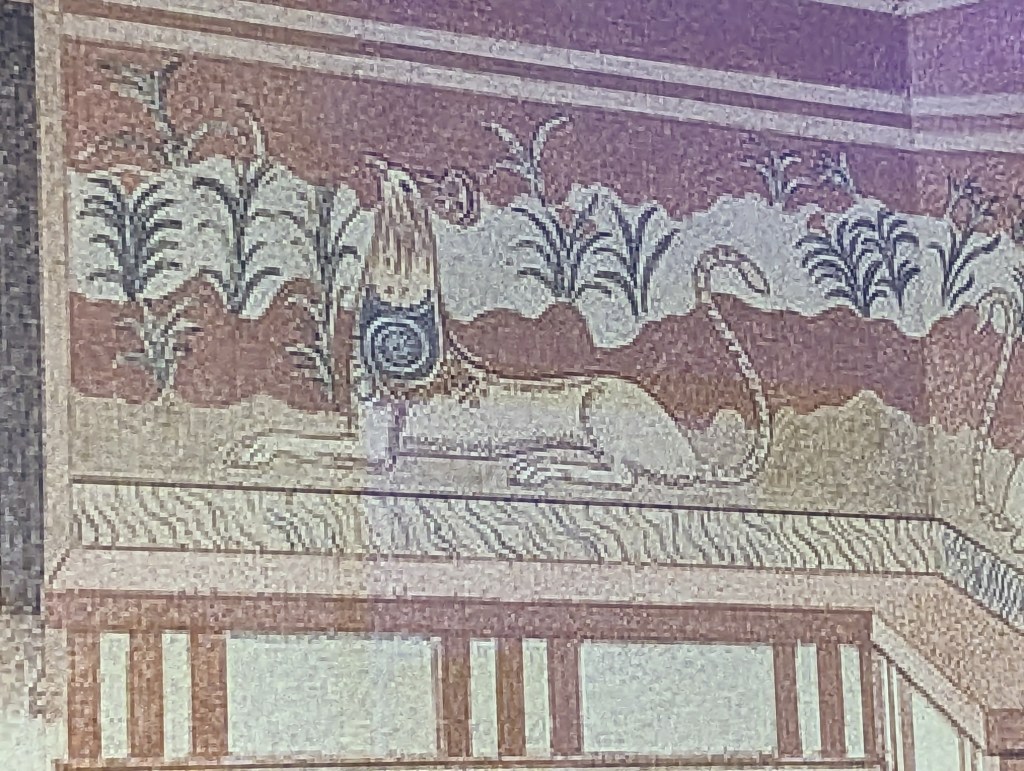

Mythological beasts also appear in Minoan frescoes and reliefs, including the Griffin, with a lion’s body and an eagle’s head. The Minoans believed the Griffin was sacred and symbolic of power, wealth, courage and prestige. It appears on the walls of the Throne Room at Knossos Palace, a chamber built for sacred ceremonials, and on other walls in the palace.

The Labrys or double axe was not a weapon, but rather a sacred symbol of the Minoan religion. In Crete it accompanied goddesses, never gods. Representations of double axes are also found in Africa and Old Europe, and are associated with the worship of Mother Earth or Great Goddess. The double axe appears on seals, rings, pottery, jewelry, frescoes, and in sanctuaries.

The second part of our excursion was a visit to a Cretan potter in the Thrapsano village. The Thrapsano potters are considered descendants of the Minoans. These potters produce the traditional Minoan storage jars known as pitharia. A potter who has produced pots for 50 years demonstrated making a pouring vessel and a pot.

Joe bravely volunteered to try his hand at making a pot. Unfortunately, it was a lot harder than it looked. 😦

After the demonstration, the potter gave us a tour of his shop, which included his two kilns, one for the small objects, and one for the much larger pots.

I would have loved to buy a large Cretan pot, maybe for a Japanese maple. Sadly, it wouldn’t fit in my suitcase. 😦

As we drove back to our ship, I enjoyed taking in the Cretan countryside.

Leave a comment